Scenes from the life of Charlemagne, Vitrail de Charlemagne [fr] at Chartres Cathedral, c. 1225

Charlemagne (Charles the Great, also known as Charles I, l. 742-814) was King of the Franks (r. 768-814), King of the Franks and Lombards (r. 774-814), and Holy Roman Emperor (r. 800-814). He is among the best-known and most influential figures of the Early Middle Ages for his military successes which united most of Western Europe, his educational and ecclesiastical reforms, and his policies which laid the foundation for the development of later European nations.

He was the son of Pepin the Short, King of the Franks (r. 751-768, first king of the Carolingian Dynasty). Charlemagne ascended to the throne at his father’s death, co-ruling with his brother Carloman I (r. 768-771) until the latter’s death. As sole ruler afterwards, Charlemagne rapidly expanded his kingdom, styled himself the head of the Western Church – superseding the popes of the time in power – and personally led military campaigns to Christianize Europe and subdue unrest almost continuously for the 46 years of his reign.

His death in 814 of natural causes was considered a tragedy by his contemporaries, and he was mourned throughout Europe; more so after the Viking raids began shortly after he died. He is often referred to as the Father of Modern Europe.

Early Life & Rise to Power

Charlemagne was born, probably at Aachen (in modern-day Germany) during the final years of the Merovingian Dynasty, which had ruled the region since c. 450. The Merovingian king had been steadily losing power and influence for years while the supposedly subordinate royal position of Mayor of the Palace (equivalent to a Prime Minister) had grown more powerful. By the time of King Childeric III (r. 743-751), the monarch had virtually no power and all administrative policies were being decided by Pepin the Short, Mayor of the Palace.

Pepin understood that he could not simply usurp the throne and expect to be recognized as a legitimate king and so he appealed to the papacy, asking, “Is it right that a powerless ruler should continue to bear the title of King?” (Hollister, 108). The papacy at this time was dealing with a number of problems ranging from the hostile Lombards in Northern Italy to the iconoclasm controversy with the Byzantine Empire.

The Byzantine Emperor had recently condemned any representation of Christ in churches as idolatry and ordered them removed. Further, he had tried to dictate this same policy to the pope and have it followed in Western Europe. As the scholar C. Warren Hollister phrases it, “the papacy had never been in such desperate need of a champion” when Pope Zachary (served 741-752) received Pepin’s letter. He more or less instantly agreed with Pepin.

Pepin was crowned King of the Franks in 751 and, in keeping with royal precedent, named his two sons as his successors. Among his earliest acts as king, Pepin defeated the Lombards and donated a significant amount of their land to the papacy.

King Pepin died in 768 and his sons ascended to the throne. Co-rule with Carloman was far from harmonious as Charlemagne favored direct action in dealing with difficulties while his brother seems to have been less decisive. The first test of their rule was the rebellion of the province of Aquitaine, which Pepin had subdued, in 769.

Charlemagne marched on Aquitaine and defeated the rebels, also subduing neighboring Gascony, while Carloman refused to participate in any of it. In 770, Charlemagne married and then repudiated a Lombard princess, daughter of the king Desiderius (r. 756-774) to marry the teenage Hildegard (future mother of Louis the Pious, r. 814-840). Following overtures by Desiderius to Carloman to topple Charlemagne and avenge his daughter’s honor, the two brothers were on a direct course to civil war when Carloman died in 771.

Military Campaigns & Expansion

As sole ruler of the Franks, Charlemagne ruled from the start by force of his personality which embodied the warrior-king ethos combined with Christian vision.

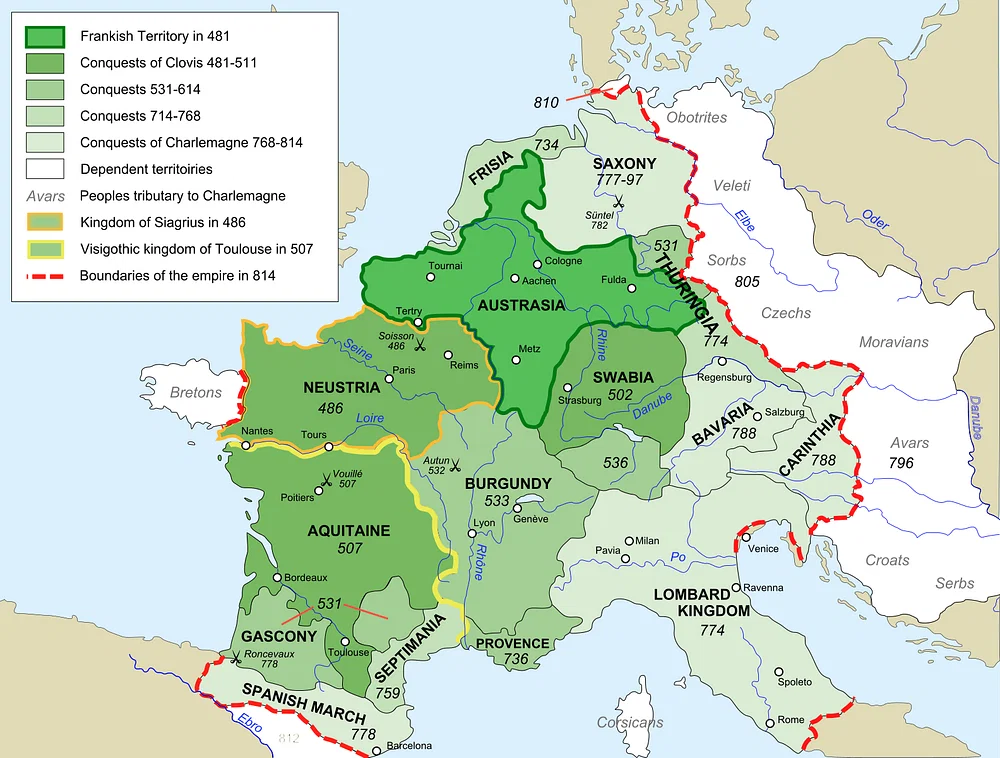

After building up his army, he launched his first campaign into Saxony in 772, beginning a long and bloody conflict known as the Saxon Wars (772-804) in an effort to root out Norse paganism in the region and establish his authority there. Leaving troops in Saxony, he turned to Italy where the Lombards were asserting themselves again. He conquered the Lombards in 774 and brought their lands into his kingdom, thereafter calling himself “King of the Franks and Lombards”, and then turned back to Saxony.

Basque unrest in the Pyrenes drew Charlemagne and his army in that direction for a number of engagements including the famous Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778 in which Charlemagne’s rearguard was ambushed and massacred, including the count Roland of the Breton March.

Between 778 and 796, Charlemagne campaigned every year in the Pyrenes, Spain, and Germania winning repeated victories. In 795, he accepted the surrender of the Avars of Hungary but, refusing to trust them, attacked their stronghold (known as The Ring) and defeated them completely in 796, effectively ending them as a people. He had also defeated the Saracens of northern Spain, establishing a buffer zone called the Spanish March, and taken the island of Corsica. His kingdom now extended through the region of modern-day France, northern Spain, northern Italy, and modern-day Germany except for Saxony in the north.

Saxon Wars

Each time Charlemagne thought he had subdued the Saxons and put their struggle to rest, they rebelled again. Prior to the Saxon Wars, the region of Saxony had been on good terms with Francia and regularly interacted with them, serving as a trade conduit to Scandinavian countries. In 772, a Saxon party was said to have raided and burned a church in Deventer in frankish lands.

In retribution for the burned church, Charlemagne marched on Westphalia and destroyed the Irminsul, the sacred tree representing Yggdrasil (the Tree of Life in Norse mythology), and slaughtered a number of Saxons on his first campaign. His second, third, and the rest (totaling 18) followed the same model of destruction and massacre. In 777 a Saxon warrior-chief named Widukind led the resistance and, although an able leader, he was as helpless to seriously challenge Charlemagne’s war machine as anyone else in Europe had been. He did, however, negotiate with King Sigfried of Denmark to allow Saxon refugees into his kingdom.

Finally, in 804, Charlemagne deported over 10,000 Saxons to Neustria in his kingdom and replaced them in Saxony with his own people, effectively winning the conflict but earning the enmity of the Scandinavian kings, particularly Sigfried who attacked the Frankish region of Frisia shortly afterwards.

Holy Roman Emperor

Throughout the Saxon Wars and his other campaigns, Charlemagne was acting entirely on his own initiative and paying very little attention to the papacy. None of the popes were complaining, however, because Charlemagne’s various enterprises coincided with their own interests or benefited them directly. It was clear by 800, however, that Charlemagne’s power exceeded that of the papacy and there was nothing anyone could do about it.

This became clear when Pope Leo III (served 795-816) was attacked by a mob in the streets of Rome and was forced to flee. The mob had been stirred up by Roman nobles who, hoping to replace Leo III with one of their own, had accused him of immorality and abusing his office. Leo went to Charlemagne for protection and, on the advice of his learned counselor, the scholar Alcuin (l. 735-804), Charlemagne agreed to accompany Leo back to Rome to clear his name, which he then did.

Charlemagne allegedly did not want to be crowned by Leo and reportedly said he would never have entered the church if he had known it would happen.

Legacy

Charlemagne ruled his empire for 14 years until his death from natural causes in 814. Loyn notes how his “force and dynamic personality were needed to create the empire and, without him, disintegrating elements quickly gained the ascendancy” (79). He had already crowned Louis the Pious as successor in 813 but he could do nothing to ensure his legacy would endure after he died.

The initial troubles for the empire, however, were due not to any backsliding or disintegrating elements but to Charlemagne’s own choices regarding Saxony decades earlier. The Saxon Wars destroyed the region, killed thousands of people, and did little else except enrage the Scandinavian kings who bided their time until Charlemagne’s death and then unleashed the Viking raids on Francia. During Louis’ reign, between 820 and 840, the Vikings struck repeatedly at Francia. Louis did his best to fend off these attacks but found it easier to appease the Norse through land grants and negotiations.

When Louis died in 840, the empire was divided among his three sons who fought each other for supremacy. Their conflict was concluded by the Treaty of Verdun of 843 which divided the empire between Louis I’s sons. Louis the German (r. 843-876) received East Francia, Lothair (r. 843-855) took Middle Francia, and Charles the Bald (r. 843-877) would rule West Francia.

Although Charlemagne himself was never affected by the church’s absurd Donation of Constantine fraud, his descendants were not as strong, and the later Carolingian Dynasty would suffer accordingly as the popes asserted their supposed political authority.

Full article in worldhistory.org

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

- 📀 Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube

- 🔥 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread

- ⚔ Come talk in the New Weekly PoC thread

- ✨ Talk with fellow Trans comrades in the New Weekly Trans thread

- 👊 Share your gains and goals with your comrades in the New Weekly Improvement thread

- 🧡 Disabled comm megathread

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory:

It should be called the Rhodesian mercenary method